Interview: Blockchains, Wall St & Economics

Howdy folks! I recently gave two interviews about the financial system, and here’s the first one to be released publicly. In this interview, Arthur Falls of the Ether Review asks why I think blockchains are so critical to fixing what’s wrong with the financial system, to ensure its safety and soundness.

It was an honor to chat with Arthur, who is also director of media at ConsenSys!

The interview is available here.

Here are some snippets / resources / additional color:

- Blockchains can bring efficiency, transparency and reduced counterparty risk to the mainstream financial industry.

- T+3 securities settlement is not a technological problem. It’s a source of substantial and unnecessary counterparty risk in the financial system, and it needs to be fixed.

- Blockchains can solve a pain point for regulators, which is that no one really knows how leveraged the financial system is today. Even the banks themselves do not know, and banks’ risk departments really do want to know.

- For the first time, blockchains can give regulators a tool for backing out the repo market’s double-counted assets to know the true solvency, in real-time, of both individual banks and the financial system as a whole.

- Rehypothecation is conceptually similar to fractional reserve banking because a dollar of base money is responsible for several different dollars of debt issued against that same dollar of base money. In the repo market, collateral (such as U.S Treasury securities) functions as base money. Collateral has taken on a “moneyness” characteristic that’s not captured in the traditional money supply measures like M0, M1 or M2. The fact that collateral has “moneyness” makes it the fulcrum point of so much of the credit creation process in recent years. (Side note: In my experience the process of credit creation in the shadow banking system is misunderstood by most—Fed proponents and critics alike.)

- Through rehypothecation, multiple parties report that they own the same asset at the same time when in reality only one of them does—because, after all, only one such asset exists. One of the most important benefits of blockchains for regulators is gaining a tool to see how much double-counting is happening (specifically, how long “collateral chains” really are). This is simply not knowable today because information is too fragmented and can’t be reconciled.

- 99+% of the time, the financial system works and there are no issues. But when there’s a run on the shadow banking system, as there was in 2008, it’s a big problem.

- The Fed acts as lender-of-last-resort for the traditional banking system, creating and injecting new money when a bank run happens in the traditional banking sector. Yet, there’s no such lender-of-last-resort for the shadow banking system—it’s not possible for the Fed to create new Treasury bonds out of thin air.

- Austrian School economists who question why the substantial increase in the Fed’s balance sheet after the financial crisis didn’t cause a big outbreak of price inflation may appreciate Arthur’s question about whether we really want to shine light onto how leveraged the financial system truly is. Speaking about the 2008 crisis, I paint the picture of the run on the shadow banking system—and the substantial credit contraction it caused—which the Fed was able to offset by expanding the monetary base. In other words, to stem the run the Fed offset the amount of credit contraction in the shadow banking system with money expansion, in order to keep the total sum of money + credit outstanding from collapsing. As of today, there’s more than $65 trillion of money + credit outstanding in non-financial sectors in the U.S., compared to just under $4 trillion of base money outstanding. That’s a lot of leverage—literally a lot of credit created on top of that base money. (Side note: I think the Fed will be able to keep offsetting credit contraction with monetary base expansion without triggering price inflation for longer than most Austrian economists believe—but, unlike other schools of economic thought, I do agree that past credit inflation has been highly damaging by distorting interest rates and causing latent capital misallocation. The effects of distorted interest rates can be masked for long periods by the continued growth of money + credit outstanding, and in the U.S. the growth in the sum of money + credit outstanding has been amazingly steady. You can track these numbers in the Fed’s Z.1 report, which comes out quarterly.)

- I reiterate my view that the financial system is still too leveraged, applauding regulators’ higher capital requirements for banks (including Basel 3, Dodd-Frank and more apparently coming), but also defending the financial industry by positing that no one wants better visibility into counterparty creditworthiness and the length of collateral chains than the risk departments of the financial institutions themselves.

- Blockchains would provide a substantial improvement in transparency over today’s reporting infrastructure, even if the blockchains are permissioned and run on closed networks.

- Regulators should, however, get involved because some of the proposed new blockchain platforms would leave some of the most critical information off the chain and regulators may later regret not having immediate access to that critical information when the new platforms are adopted.

- Permissionless blockchains, such as Bitcoin and Ethereum, will successfully scale over time, in my view. But today, the financial industry needs technology that offers much higher throughput than Bitcoin and Ethereum were designed to provide. Many commercial blockchain platforms are giving up transparency and immutability in exchange for high throughput. But they’re still such an improvement over the status quo, and I’d encourage even bitcoin maximalists to appreciate the improvement—even if, as I believe, blockchain is an intermediate step toward infrastructure that will ultimately be decentralized. Permissionless ledgers and denationalized money will probably ultimately win out because they’re cheaper and have no counterparty risk, but I believe that’s 20 years away and a lot of intermediate-step blockchain adoption (and resulting improvement) will take place between now and then.

- When TCP/IP came along, companies at first took baby steps by adopting intranets inside walled gardens before they fully engaged in the Internet. With blockchains, by analogy, companies are taking cautious intermediate steps to adopt centralized, walled-garden versions first. And just as the true power of the Internet came from companies opening those walled gardens to the outside world, I believe the same will happen with blockchains over time. Truly decentralized, permissionless networks will win out because they are superior for so many reasons, but they’re not ready for prime time yet and the adoption process will take years. The end users—people using the payments system or transferring assets—want frictionless networks and they will create incentives for the financial industry to adopt them.

- Switching costs for the financial industry are very high, because blockchain technology architecture is so different from current IT infrastructure.

- The blockchain industry should dial back expectations about how fast implementation will take place. It’s analogous to the cable industry, where in 1998 proponents believed that the Internet would challenge cable TV. It took nearly 20 years for the visionaries to be proven right.

- That said, I see many markets where blockchains will have huge success immediately—markets that still run on fax machines and need IT upgrades anyway, or markets in which most of the securities that will be outstanding in 10 years haven’t been issued yet. I’d expect public equities markets to be the “caboose” for blockchain adoption. It may take ~20 years for a complete switch-over of all financial markets to blockchain technology.

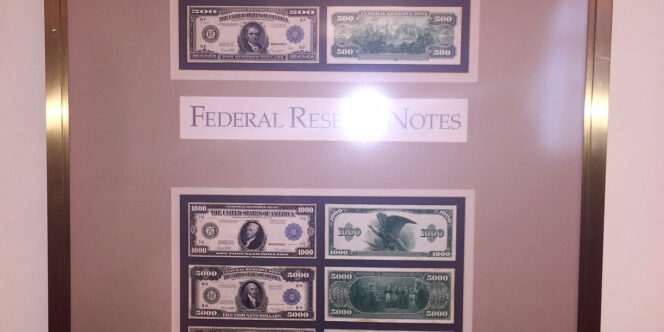

- Here’s the picture I mentioned of the $10,000 bill issued by the Fed in 1918, which hangs in the Fed’s boardroom and which I photographed during the Fed’s fintech conference on June 1, 2016. Just imagine what that’s worth today! I suspect it was used for inter-bank settlements rather than circulated on the streets. How fitting that today, some central banks are looking into blockchains for this very task!

- Resources I mentioned during the interview:

- Doug Noland, author of the blog Credit Bubble Bulletin, from whom I learned about the “moneyness” of collateral in the shadow banking system. Every Saturday morning I read Doug’s weekly commentary. He has chronicled the credit bubble for years, and historians will someday widely cite his work. His website is here.

- Manmohan Singh, senior IMF economist, who has done tremendous work on rehypothecation and collateral chains. Here,here, here, here and here are among the many insightful writings by Singh on this topic.

- Pete Rizzo, East Coast editor of Coindesk, whose terrific column I mentioned regarding the 1998 Wired Magazine cover that touted the imminent challenge of cable TV by the Internet. Nearly 20 years later, it’s finally happening. Pete’s column is available here.

- Thanks for listening! And thanks again, Arthur, for a fun interview!

Founder/CEO Custodia Bank. #bitcoin since 2012. 22-yr Wall St veteran. Not advice; not views of Custodia Bank!

Disclaimer

This web site is limited to the dissemination of general information, investment-related information, publications, and links.

Please consult important additional information and qualifications HERE.

View Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

Connect with me on Social Media

Search Posts

Categories

Recent Posts

- How To Keep The Bitcoin Strategic Reserve From Morphing Into A Bailout Fund January 28, 2025

- The Engineering of Bitcoin October 1, 2023

- Here Come The Fintech Banks!! July 21, 2023

- Why Defending The Right of States to Charter Banks Without Federal Permission Is Critical April 17, 2023

- Why Can’t We Just Have Safe, Boring Banks? March 21, 2023