My Interview by Bob Murphy: Financial Markets, Economics, EMH & More!

Republished with permission from the June 2016 edition of the Lara-Murphy Report, a subscription newsletter available here.

Dr. Bob Murphy, who conducted the interview, is a truly gifted teacher and one of my favorite economics professors. During my tour of alternative economic schools of thought after the financial crisis, it was a pleasure to learn about the Austrian School of economics from Dr. Murphy.

In this interview we touch on negative interest rates, whether the efficient markets hypothesis holds true in reality, and what’s happening with Europe’s banks. We cover what I think the Austrian School of economics has gotten right and—importantly—some things it has missed as well. (Note this interview took place in early June so did not cover the impact of Brexit.)

Again, this blog does not provide investment advice. Caveat emptor! Please read important disclaimers here and here. Thanks for stopping by!

Lara-Murphy Report: We interviewed you for the inaugural issue of the Lara-Murphy Report! But for the benefit of our new readers, how did you learn about Austrian economics?

Caitlin Long: Bob, I learned a lot from your online classes! It didn’t take me long to discover you! But Tim Geithner was actually the spark that got me started in Austrian economics. He was Treasury Secretary then. During a 2008 interview after the financial crisis began, he admitted that interest rates were too low before the crisis and insinuated that was a cause of the crisis. Then, a few days later, I heard him argue that interest rates should be even lower. His contradiction got me digging! So I called a friend and former client—one of the best thinkers on the buy-side—to brainstorm. I remember realizing out loud, “I need to learn how the Federal Reserve works. That’s the key to understanding how this happened.” My pal told me to start reading about Austrian economics, and the rest is history. Since then I’ve explored other alternative schools of economic thought, too, but I continue to believe the Austrians have the best assessment of what’s going on. The Austrian School isn’t perfect—for example, I think its misunderstanding of the shadow banking system caused it incorrectly to predict hyperinflation after the financial crisis—but I think its diagnosis of the problem is by far the best among economic schools of thought.

I agree with Austrians that the interest rate is the most important price in any economy, because it’s the traffic signal that directs entrepreneurs where to invest their capital. When interest rates are artificially distorted, capital misallocation happens. Wealth is destroyed. Interest rate distortions can persist for decades as living standards are maintained through borrowing—and that’s we’re living through today. Globally, we’re eating our seed corn by borrowing against the equity on our balance sheets. Eventually, economies run out of balance sheet capacity to keep borrowing, and then a reset happens—but again, this process can take decades.

Another way to phrase this is that Austrians believe balance sheets really do matter. It became clear on my journey of economic exploration that other schools of thought pretty much ignore balance sheets. Their answer is almost always to borrow/stimulate more, without considering the cost of distortions. Austrians believe in preserving capital to grow wealth.

Bob, I’ve heard you say that you became an Austrian because it’s the only school of economic thought that has a capital theory—I fully agree!

LMR: Last time we talked, we asked you about low interest rates. So now we have to ask: What’s the impact of negative interest rates on the financial sector?

CL: Negative interest rates are a symptom of overleveraged balance sheets—a signal that there’s very little borrowing capacity left in an economy (whether in the household, business or government sectors). Since about 2012, I’ve expected that interest rates would turn negative eventually—and I think rates ultimately will go negative in the U.S., too. In fact we have already experienced brief periods of negative T-bill rates in the U.S. I see no reason to believe the 35-year trend of declining yields on 10-year Treasury bonds will break, because the fundamental driver of this trend is higher debt—and I don’t see debt growth stopping anytime soon. That doesn’t mean rates will be a one-way street lower—rates will go up periodically without breaking the larger downward trend. In fact, every time the 10-year Treasury yield has risen since 1981, it dropped again before reaching its prior peak (on a monthly basis). Lower lows and lower highs—for 35 years! Ask a mainstream economist to explain what why that hasn’t mean-reverted yet!

Obviously, negative interest rates aren’t good for the financial sector, whose business model is generally to earn a spread between asset returns and borrowing costs. Banks are being squeezed by higher capital requirements on both sides of that equation, while also bringing down their leverage. That’s painful for banks. An example is Switzerland, which was early to experience negative interest rates and whose government bond yields are negative out to the longest maturities relative to others. For a couple of years now, Swiss banks have quietly turned away corporate depositors and charged all kinds of new fees to avoid losing money. Most banking professionals assume that negative interest rates are temporary and will mean-revert soon, but I don’t agree. They can persist longer than most of us think they can.

LMR: Many Austrian-friendly investors—such as Mark Spitznagel—have been warning that a stock market crash is imminent. How should people think about U.S. equities? There’s a popular school of thought that says the market is always valued according to the best information, and so regular Joes have no business second guessing the current level of the Dow.

CL: Well, I’m not in the business of giving investment advice so won’t predict anything here, but I’ll try to educate your readers about what has been happening so readers can make their own predictions. What you’re really asking is whether the “efficient markets hypothesis” (EMH) is valid. I think the answer is yes, it is—BUT ONLY IF interest rates are set on the free market by the voluntary interaction of savers and borrowers. When interest rates are artificially distorted, EMH doesn’t apply. I was 15 years into a Wall St career before I figured out EMH isn’t relevant because interest rates aren’t set by free markets. To this day, most of Wall Street still adheres to EMH because most trading models are still based on it (for example, the Black-Scholes option pricing model presumes efficient markets). The models aren’t wrong—they just don’t reflect today’s reality because markets cannot be efficient when interest rates are artificially distorted.

So what does this mean for the stock market? Is it overvalued? I could easily make arguments both ways—for example, since an asset’s value is the discounted value of the cash flows it generates, I could argue that all assets are overvalued since discount rates are artificially low. Conversely, I could also argue that the way financial markets price credit risk will be turned on its head when governments eventually run out of debt capacity, in which case money will migrate from public to private assets—so stocks may in fact be undervalued. No one knows how markets will play out because no one knows the sequence of events here in the US or overseas. We just know that prices are distorted—but that doesn’t necessarily mean they will revert anytime soon! As a student of economic history, I realize these distortions have existed for much longer I’ve been alive—and longer than my parents were alive, too. Yes, the distortions are bigger than ever today. But some Austrians have been predicting a dollar crash for decades and it hasn’t happened yet.

I think the most interesting question is why these distortions have been able to persist—that’s something about which I’ve done a great deal of thinking. In essence, the US entered its period of inflation (of money and credit) with an incredibly strong balance sheet—and we’ve been drawing down the economy’s equity for decades to support new borrowing. The fact that the US economy’s balance sheet still has equity (i.e., assets > debt) explains why a big correction in the US dollar hasn’t happened yet.

LMR: You brought to our attention years ago an analysis that showed even a modest rise in Treasury yields would render the Fed insolvent—meaning its assets would have a lower market value than its liabilities. Do you know what that analysis looks like today? Do people in the markets worry about things like this?

CL: Yes, that description still holds true. The Fed created what we call a “duration mismatch” by getting into the business of maturity transformation with Operation Twist in 2011, when it started buying long-dated bonds to bring down long-term interest rates. This means the assets on the Fed’s balance sheet are longer-dated than its liabilities. At my last calculation, the duration mismatch on the Fed’s balance sheet was about 5 years—in other words, the duration of its assets was as about 5 years longer than the duration of its liabilities. The Fed’s balance sheet as of June 2, 2016 had $40bn of equity capital supporting assets of $4.46 trillion. In other words, the Fed’s balance sheet is 111.3x levered. The Fed doesn’t mark its assets to market value, so that leverage number appears worse than it actually is on a market-value basis. But still, mathematically, it would not take a large increase in interest rates for the Fed’s equity capital to be consumed by the declining market value of its bond portfolio.

You ask whether people in markets worry about this, and I think the answer is only a handful of people worry about it. The typical response is to point out that the Fed can write checks on itself by doing more QE if it needs to—but that actually exacerbates its leverage. I’d put this in the category of a distortion that can persist for years, with very few caring about it—until someday it matters a lot.

LMR: We keep reading doom and gloom reports on Deutsche Bank. Is this a one-off fluke or is there something more fundamental that’s awry?

CL: I can’t opine on a particular bank, but it’s a fact that Europe’s banks have been more leveraged than America’s banks for quite a long time—and I think America’s banks are still too leveraged as well. But, again, this does not mean the situation will correct anytime soon. Notice a theme in my answers—lots of distortions, but they’re not new and Keynes was right when he said markets can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent. I don’t know what will catalyze a return to rationality, or when! In the meantime, we need to work to feed our families! We can’t hide under a rock, nor should we! The right way to think about these issues is to recognize that they exist, and do your best to adjust for them when putting your hard-earned capital to work.

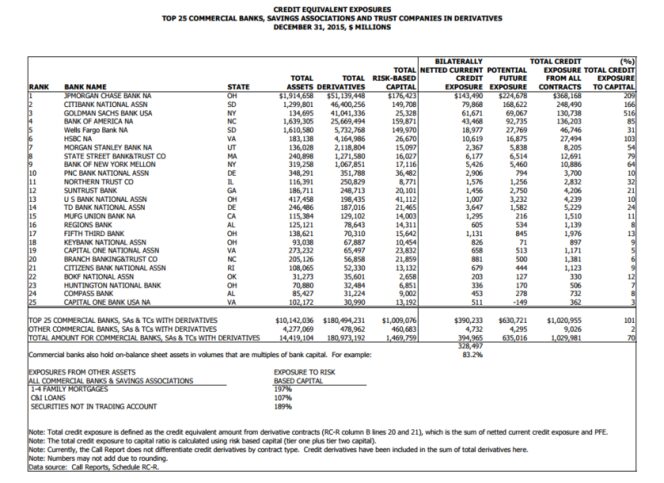

I’ve always pointed to one simple fact about Deutsche Bank, which has been true for a while—Deutsche’s derivatives portfolio was roughly the same size as JPMorgan’s for several years, but Deutsche had about one-third of the equity capital of JPMorgan (meaning Tier1 + Tier2 capital). Recently, this situation has improved slightly—at year-end 2015, Deutsche’s derivatives notional was EUR 41.94 trillion on total risk-based capital of EUR 60.98 billion, compared to JPMorgan’s at $51.14 trillion and $176.42 billion, respectively. So just on this simple measure you see that Deutsche is a lot more leveraged than JPMorgan. Now I’m not opining about JPMorgan’s leverage—if you look it up in the OCC’s database, you’ll see that JPMorgan’s credit exposure from derivatives alone was 209% of its total risk-based capital at year-end 2015. JPMorgan is one of four US banks whose credit exposure from derivatives alone exceeds its total risk-based capital (the others are Citibank NA, Goldman Sachs Bank USA and HSBC NA). Please don’t make any decisions based on these facts—I expressly disclaim any and all advice on what to do here! Caveat emptor! And again, none of this is new.

It’s clear to me that regulators are working to fix this—they face a delicate balance between clamping down on bank leverage and preventing an economy-wide credit contraction. For example, on June 3rd the Wall Street Journal ran a headline story outlining a “probable” increase in the capital requirement for the biggest 8 banks in the US—on top of the myriad increases they’ve already had. Only time will tell if the regulators’ strategy of steady, consistent increases in banks’ capital requirements will have been the right one, or whether they will have been too slow. Remember that Mises said, “Economics recommends neither inflationary nor deflationary policy.” In other words, deflationary policy is not the right response to a prior inflation. What’s already done is done. The US economy has $61.2 trillion of credit outstanding in non-financial sectors—that’s what’s already done. More of that credit has taken on “moneyness” in the market for collateral than we Austrians like to admit—and I’d argue that most Austrian definitions of money mistreat much of that credit, which has taken on “moneyness” in the shadow banking system (e.g., Treasury/GSE debt functions as base money in these markets). It’s an area of research that’s sorely needed in the Austrian economics field. If you grant my argument, just for this moment, then you see why I believe regulators have so far have executed a successful balance between bank deleveraging and credit deflation. That’s a tough balancing act, indeed!

Founder/CEO Custodia Bank. #bitcoin since 2012. 22-yr Wall St veteran. Not advice; not views of Custodia Bank!

Disclaimer

This web site is limited to the dissemination of general information, investment-related information, publications, and links.

Please consult important additional information and qualifications HERE.

View Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

Connect with me on Social Media

Search Posts

Categories

Recent Posts

- How To Keep The Bitcoin Strategic Reserve From Morphing Into A Bailout Fund January 28, 2025

- The Engineering of Bitcoin October 1, 2023

- Here Come The Fintech Banks!! July 21, 2023

- Why Defending The Right of States to Charter Banks Without Federal Permission Is Critical April 17, 2023

- Why Can’t We Just Have Safe, Boring Banks? March 21, 2023